We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

In his day, Harry Sylvester was viewed as an important Catholic literary voice—a fine writer and a sharp observer, whose description is often precise, poetic, and powerful. But because he focused on contemporary cultural and social concerns instead of the faith itself, he automatically dated his work and destined it to be forgotten.

Helping in my search-and-rescue mission for decent fiction writers, I have been sent two novels by the largely forgotten Harry Sylvester.

Helping in my search-and-rescue mission for decent fiction writers, I have been sent two novels by the largely forgotten Harry Sylvester.

Sylvester was born in 1908 in New York City. His father was heavily involved in local politics. After graduation from high school he attended Notre Dame where he played football for the famous Knute Rockne. His writing career began in sports journalism and developed into short stories and novels with a trilogy of novels rooted in his Catholic faith.

In his day, Sylvester was viewed as an important Catholic literary voice. Friendly with fellow Catholic writers, J.F.Powers, Richard T. Sullivan, and Ernest Hemingway, he was sympathetic to the peace and justice concerns of many Catholics at the time and developed a reputation for being critical of the Catholic hierarchy. By the 1950s Sylvester had divorced his wife Rita, whom he had married in 1936, and he formally renounced the Catholic Church and became a Quaker.

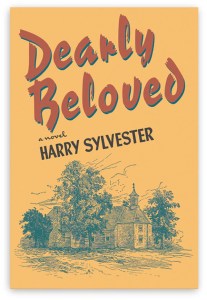

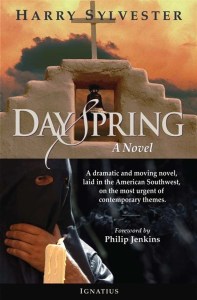

The first of his Catholic novels—Dearly Beloved—is set in Southern Maryland in the 1930s, where a community of Jesuits struggle to establish a co-op for impoverished black fishermen, while also dealing with the hypocrisy and racism of their white congregants. Set in New Mexico, the second in the trilogy, Dayspring, follows the investigations of an atheist anthropologist named Spencer Bain. The story chronicles Bain’s research into the Hermanos de Luz (or the Penitente Brotherhood) and his subsequent conversion to Catholicism through the process. Moon Gaffney—the third novel with a Catholic setting—follows the story of a young man in New York who struggles to reconcile his religious beliefs with his political ambitions.

The first of his Catholic novels—Dearly Beloved—is set in Southern Maryland in the 1930s, where a community of Jesuits struggle to establish a co-op for impoverished black fishermen, while also dealing with the hypocrisy and racism of their white congregants. Set in New Mexico, the second in the trilogy, Dayspring, follows the investigations of an atheist anthropologist named Spencer Bain. The story chronicles Bain’s research into the Hermanos de Luz (or the Penitente Brotherhood) and his subsequent conversion to Catholicism through the process. Moon Gaffney—the third novel with a Catholic setting—follows the story of a young man in New York who struggles to reconcile his religious beliefs with his political ambitions.

Sylvester was a fine writer and a sharp observer, whose description is often precise, poetic, and powerful. He captures character and dialogue well and crafts an intriguing-character based plot. The novels move slowly by the standards of contemporary fiction and much of the language and references are dated. What is happening, for instance, when a character “puts on his Chesterfield”? Is that a cigarette, a town in England, a sofa? I’m guessing from the context that it’s a hat. Nope. It’s a velvet-collared overcoat.

The dated settings add to the novels’ appeal by providing a glimpse into 1940s American Catholicism. However, the settings and concerns are now eighty years old, and it is difficult to connect with Sylvester’s protagonists. The worries of Catholics in New York or Maryland in the 1940s don’t worry me, nor are they the concerns of activist Catholics today, who have moved on from workers’ rights and economic equality to women’s ordination, the LGBTQ agenda, and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.

What interested me about both Dearly Beloved and Moon Gaffney is that both novels are concerned not so much about Catholic doctrine, devotions, and worship as about Catholic social action. The Jesuits in Dearly Beloved are struggling to combat poverty, racism, and the institutional complacency and hypocrisy of Catholics. In Moon Gaffney, the young Catholics in New York interact with Dorothy Day and her group of social activists and are more concerned with politics and social injustice than the core of Catholicism—her supernatural doctrines, heart felt devotions and divine worship. They’re concerned about getting to Mass, but theirs (and the Jesuits in Maryland in the first novel) is a cultural, inherited Catholicism concerned more about changing society than saving souls.

What interested me about both Dearly Beloved and Moon Gaffney is that both novels are concerned not so much about Catholic doctrine, devotions, and worship as about Catholic social action. The Jesuits in Dearly Beloved are struggling to combat poverty, racism, and the institutional complacency and hypocrisy of Catholics. In Moon Gaffney, the young Catholics in New York interact with Dorothy Day and her group of social activists and are more concerned with politics and social injustice than the core of Catholicism—her supernatural doctrines, heart felt devotions and divine worship. They’re concerned about getting to Mass, but theirs (and the Jesuits in Maryland in the first novel) is a cultural, inherited Catholicism concerned more about changing society than saving souls.

That Sylvester eventually left his Catholic faith is not surprising. That his fiction is largely forgotten is also not surprising. This is because he focused on cultural and social concerns instead of the faith itself. Christianity is a cultural and social phenomenon, but the faith’s interaction with culture is secondary to the religion itself. This is not to say that religious fiction should be pious devotional literature shrouded in a story, nor must the story always be set in a religious milieu, and we do not want a sermon disguised as a story.

A longer essay would compare Sylvester to Flannery O’Connor. Arguably, O’Connor’s rural Southern settings are even more dated and obscure than Sylvester’s Maryland, New Mexico, and New York. If Moon Gaffney (a Catholic young man from 19040s New York) now seems inaccessible and irrelevant, should not the rednecks, schoolgirls, freaks, and weirdoes of O’Connor’s fiction seem even more inaccessible and unreal?

Not in my opinion, and here is the perennial paradox: In writing about relevant, contemporary Catholic concerns, Sylvester automatically dated his work and destined it to be forgotten. O’Connor, on the other hand, is not primarily concerned about inequality for farm workers, racism, or discrimination against foreigners. All these elements are in her stories, but they are not her focus. Instead her sharp eye, sharper wit, and wisdom cut straight to the point. She is writing not about surface concerns, but about the human condition—the heart of darkness and the light of Christ, and that is why her writing endures.

Not in my opinion, and here is the perennial paradox: In writing about relevant, contemporary Catholic concerns, Sylvester automatically dated his work and destined it to be forgotten. O’Connor, on the other hand, is not primarily concerned about inequality for farm workers, racism, or discrimination against foreigners. All these elements are in her stories, but they are not her focus. Instead her sharp eye, sharper wit, and wisdom cut straight to the point. She is writing not about surface concerns, but about the human condition—the heart of darkness and the light of Christ, and that is why her writing endures.

Perhaps I am being unfair to Sylvester, but it seems like this Catholic heart is missing from his vision, and thus his work, while finely crafted, misses the mark for Catholic fiction. Nevertheless, I recommend his novels. Dearly Beloved and Moon Gaffney have recently been republished by Angelico Press, and Ignatius Press published Dayspring in 2009. Now who is going to bring us a new edition of his short story collection, All Your Idols?

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “Harry Sylvester, headshot from newspapers (c. 1947),” courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Go to Top

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News