We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Saul Bellow’s protagonist Artur Sammler is both witness and survivor to the central event in his own time: the attempt on the part of Hitler and his henchmen to eradicate European Jewry. But even though the novel takes place in a different time and place, behind those contemporary times are the ghosts from that World War II era and Sammler’s own suffering, which informs the novel with extraordinary force.

In the kingdom of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. —attributed to Desiderius Erasmus

“Men need, and it is granted to them, to confirm one another in their individual being by means of genuine meetings. But beyond this they need, and it is granted to them, to see that the truth, which the soul gains by its struggle, is flashing up for the others, the brothers in a different way, and equally confirmed.” —Martin Buber, “Limits,” from Chapter II, “I and Thou,” The Way of Response

“Through Fifteenth Street ran a warm spring current. Lilacs and sewage. There were as yet no lilacs, but an element of savage gas was velvety and sweet. . . and it got to one—oh, deeply, too . . . . But then ten or twelve years after the war . . . creatureliness crept in again. Its low tricks and doggish hind-sniffing charm. So that now, really, Sammler didn’t know how to take himself. He wanted, with God, to be free from the bondage of the ordinary and the finite. A soul released from Nature, from impressions, and from everyday life. For this to happen, God Himself must be waiting, surely . . . . Eckhardt said in so many words that God loved disinterested purity and unity. God Himself was drawn toward the disinterested soul. What besides the spirit should a man care for who had come back from the grave?” —Saul Bellow, Mr. Sammler’s Planet

“Hello God; it’s me, Artur Sammler.” —Coda to Mr. Sammler’s Planet

I. Years Ago….

And as a hardly aspiring undergraduate, my advisor and literature professor was the mannered Oxonian Dame Sarah Keith. My first essay assignment led me to her office for consultation. She was kind and suggested it would be good manners for me to cite my thesis statement at the beginning of the essay rather than the bottom of the second page. It was good advice. I’ve never acquired Oxonian manners but came to love that scholarly woman dearly and miss her every time I sit down to write “something.” We read books together.

This one’s for you Dame Sarah; it would be fun to sit in your “rooms”once again and chat and share the tea you taught me how to pour….

I have been forever after “mother”.…

II. Thus:

Over a three-day period in June, 1969, about the time three American astronauts were vectoring their way to a moon landing, Artur Sammler, the protagonist in Saul Bellow’s novel Mr. Sammler’s Planet, awakened the morning of the first day. He’s an emigré from Poland and London and a Holocaust survivor from World War II, a time during which his wife and many others were murdered before his eyes. It’s a traumatic experience for a man now living in New York. He’s isolated and surrounded by a plethora of tragic-comic characters who exemplify the derangement of the contemporary American soul, its ambiguity and turbulent lack of morality. With that context in mind, Artur Sammler is a Jewish elderly man demonized as “vermin” during the war, reduced to an “It,” or sub-human, but as a man of insight is aware that his human understanding and subtle analysis of contemporary culture has become deprived of an existential dialogue Martin Buber references as “I” and “Thou.” During the course of those three days, Artur Sammler engages in a spiritual struggle which includes an acceptance of an “I-Thou” genuine meeting which also reveals his wisdom gained from a long life of suffering. Called to be less than a victim and more as a spiritual guide, his struggle is heroic in as much as he refuses to surrender his life to despair. Such would be a violation of the “I and “Thou” contract.

III. The First Epigram….

The first epigram on the title page is a translation from the Latin which if I have a good understanding of Erasmus, his Latin quote is based on a Hebrew excerpt: “In the street of the blind, the one-eyed man is called the Guiding Light.”

Saul Bellow does not use the proverb as an epigram to his novel Mr. Sammler’s Planet, but it’s still a fine idea upon which the novel is built. Sammler, a tall elderly Jew, is a one-eyed man born in Cracow and a man who still preserves his Oxonian manners while looking back on what he remembers of the pleasures of England in the twenties and thirties before the civilized world collapsed. He was acquainted with the Bloomsbury folks and H. G. Wells, but with the war came a time in which he survived the Holocaust. A point needs to be made here, which is to argue that it’s a bit of pigeon-holing to classify Bellow’s novel as a Holocaust novel even if Sammler is a Polish survivor. Perhaps there’s more to it when he reader arrives at the “Thou” found in the conclusion.

As for the one-eyed character, Sammler, he is both witness and survivor to the central event in his own time: the attempt on the part of Hitler and his henchmen to eradicate European Jewry. But even though the novel takes place in a different time and place, behind those contemporary times are the ghosts from that World War II era and Sammler’s own suffering, which informs the novel with extraordinary force.

Against the times so terribly out of joint, Bellow and his spokes-person offer a neoconservative critique: Sammler, educated to love high culture and who in his philosophical maunderings, opposes his 1969 world, which acknowledges thoughtlessly the rights of everybody while the bonds of church and family weakened. Bellow does not spare his reader the details. Trying to find a working phone booth in New York is to walk into a small room become an outdoor urinal. Sammler’s reflections wonder when and where and why it all went wrong. Would it be true that Puritanism has finally been defeated by the dark Satanic mills which offer emancipation but also a world turned upside down with the 1960s sexual revolution?

When the novel opens, then, Mr. Sammler is also wakening to begin another day but not just wakening but to be “conscious,” which in terms of the novel means time to be “conscious” of one’s own place in life, history, God’s cosmos, and which in New York seems to have become another Sodom and Gomorrah, a world populated by a plenitude of crazy people, a world becoming more and more mad and the “soul,” poor bird caged..

IV. The Second Epigram And Some Notes On Martin Buber’s I and Thou And The Un-burning Bush….

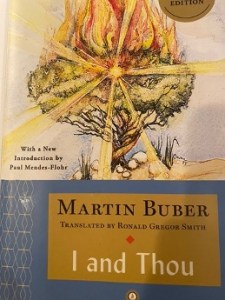

Considered one of the seminal theological texts from the past century, Martin Buber’s I and Thou was published first in 1923. It’s a slim book surveying the meaning of the relationship between our human life and God, our human life and others, and the dehumanizing currents and tensions in modern life and in which moral judgements are dominated by an “I-You” or “I-It” word pair.

Buber characterizes the existential dialogue in the latter two word pairs as “faced” by no “Thou”; he who lives with “I-It” alone is sternly capable of objectification, subduing, with no thought of the another’s spirituality or all-becoming transcendence. Understood in context, then, an “I-It” relationship leaves the “It” powerless if not capable of extermination as if “vermin.”

In a word, genocide.

History is testimony, is evidence. Care must be rendered since 20 years later the Holocaust challenged Buber’s view of man and God as dialogical partners. If God and man are bound together as if in an eternal dialogue how then to explain God’s silence in the years of the Holocaust? Or is it possible that this historical Holocaust provides a comforting answer to a more profound faith in God not only for Judaism but for Christianity. I and Thou in that respect is a sort of oracular pronouncements or “call” for a divine encounter in a post-Holocaust world grown indifferent. If so, I and Thou and its argument for divine encounter rest upon a proper response, a proper meeting.

There’s a difficulty here and that lies with the recognition by Jews and Christians in their shared belief in an all-powerful and all-righteous God. The difficulty lies in the lack of mediation in Judaism, apart from commandments and laws, compared to the mediating figure of Jesus in Christianity. In the former, it could be argued, believers are never enjoined to meet the Absolute personally; with the latter, the divine-human encounter becomes understandable and profoundly personable.

For Buber the issue, then, is a poetic meditation on the quality of human relations which leads him to address an overarching concern in an age in which human “worth” is every increasingly measured by economic utility and professional and social status which Artur Sammler pointedly refers to as “as the triumph of Enlightenment.” The point is that the more we judge and relate to other people by such objectification criteria the effect is to reduce them to a “You,”an object, a mere cog. The “You” in that respect is understood to be a “He” or a “She” and is less a degeneration than an “It” albeit both are “objects” that can be manipulated for purposes held by the “I”.

Buber’s point is that these word pairs are not abstract conceptions but ontological realities that can be represented in discursive prose, even in a novel.

But as might be expected, questions of profound significance emerge which include, I would argue, Buber’s argument that evil is a privation of dialogue about which the solution is an attempt to restore the broken dialogue with the evil-doer. How one might have accomplished such with Adolph Eichmann involved as he was with administering a system of officially-sanctioned genocide, such one might imagine is the disjunction between non-utopian politics and utopian politics, the wise children of darkness versus the foolish children of light.

Buber thus acknowledges the existential abyss that exists between an “I” and a “You” which can degenerate into an “I” and “It” to the extent that the meeting between and “I” and an “It” loses all sanctity. Consider for a moment when the “other” in the dialogue has been reduced and deprived of any kind of divine fullness, stripped both figuratively and physically which Buber says “shuts us of from the light of heaven.”

The existential dialogue between the word pairs therefore holds no promise of enhanced human dignity (of which it is our contractual duty to uphold) but illustrates what existence is like if the traditional social and ethical standards are shorn of footing. The “I” thus holds no loving responsibility for the “Other” and any hope for sacred dialogue between between the “I” and the “Other” degenerates.

If we think of this dialogically, a Downs Syndrome child, based upon the modern faith in enlightened progress, holds no promise of enhanced human dignity and if the social and ethical standards are again shorn of firm footing, how easy it is to follow with inner conviction that a very gentle and quiet death without painful convulsions is the “right thing to do” which is a bit like putting a sick pet to “sleep.”

The morality, however, is filled with anomalies and contradictory subjectivities such as “prevention of unbearable suffering.” And we know this to be the case today in the Netherlands where the already slippery slope has become more slippery since Dutch doctors have been euthanizing patients for over three decades and where over 50% of those doctors agree that parents do not need to be involved in the decision to end their impaired child’s life. Buber’s response can be understood when he writes in I and Thou that “love is responsibility of an I for a You and nothing should intervene between I and a You” (71). When something intervenes, a subjectivity, for example, then the sacred dialogue between an I and a You disintegrates.

But with the implicit knowledge that inter-human meetings are a reflection of the human meeting with God, an “I” with “Thou,” Buber insists that regardless of the infinite abyss between an “I” and a “Thou” a dialogue between man and God is possible and we live in the currents of universal reciprocity, inscrutably involved.

Buber references the disjunction as injury between man and man but also the “being” called “man” and the source of his existence. What’s left in the hours in which we live is silence and stammering until we address the eternal “Thou” which offers reconciliation anew.

Turn we then more precisely to the 2023 centennial edition of Buber’s I and Thou.

This fine book has a cover design of a desert bush with flames burning fiercely from the top but at the center is a bright spot of light radiating outward with six rays. It’s an icon, of course, and a powerful devotional one: miraculous energy, sacred light, purity, love and clarity, but also revealing Moses’ reverence and fear before the divine presence, the “Thou” proclaimed by Buber and the “Thou” Who identifies Himself to Moses as the God of the patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and that He is Yahweh.

This fine book has a cover design of a desert bush with flames burning fiercely from the top but at the center is a bright spot of light radiating outward with six rays. It’s an icon, of course, and a powerful devotional one: miraculous energy, sacred light, purity, love and clarity, but also revealing Moses’ reverence and fear before the divine presence, the “Thou” proclaimed by Buber and the “Thou” Who identifies Himself to Moses as the God of the patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and that He is Yahweh.

One might better call it “The Un-burning Bush.”

God and Moses are meeting but apart from the meeting there’s the theophany in which we understand that the blazing bush is an icon of the divine found in a physical sense but also a sacramental window into God’s spiritual energy.

Surely to come upon a burning bush in daily life would be an unusual encounter but to come upon a burning bush that doesn’t extinguish self into ashes would be a supernatural encounter, a revelation characterized by the present participle “un burning.”

And for Buber it’s not religion per se but religiosity, about which he makes important distinctions, the former having become calcified.

One might look more deeply for a word as to “what” is being revealed to Moses or to “what” Moses sees but the voice from the bush is God’s. The meeting is, however, an inter-human meeting between an “I,” Moses, and the awesome holiness of God’s divine nature, “Thou.” What needs to be learned is the proper response which might include the pious act of taking off one’s sandals. The encounter for Martin Buber also reveals the infinite abyss between God and Man before the Incarnation but regardless of the abyss there is a dialogue between God and Man which is possible but only if the response is a reciprocal “I” with “Thou” in sanctity and understood as a numinous presence which allows the “I” to glimpse eternity, to what is sometimes called the “uncreated energy” of God before the creation.

That might take some thought.

How, then, to respond?

Not in the enlightened modern way.

If the experience were that of either Camus or Sartre the result would be a negligible meeting between an absurd man and an absurd world.

If it were that of Ivan Karamazov it would be an encounter with God but not an acceptance of God’s created world.

But for Martin Buber, the encounter with a burning bush in this world is God’s directing man toward action in this world such as leading the Hebrew tribes out of Egypt. It’s an unceasing dialogue between heaven and earth, “I” and “Thou,” call and response.

Rather than impersonal man moving aimlessly in an impersonal universe (K in Kafka’s novel comes to mind), for Buber God has not withdrawn but still personalizes all that He loves.

Turn we again to Saul Bellow and his novel Mr. Sammler’s Planet, which can be read, I suggest, as a conversation with Buber’s I and Thou.

V. The Third Epigram Context And Seventy-Two Hours….

It’s not unique to Saul Bellow since a forerunner was Henry James, who created in his “psychological” novels a framing structure around what he called a “central consciousness,” a governing intelligence, a character that he believed the narrator would stay with throughout the novel, more so, a prescient and intelligent character through whose mind most of the story would be told which meant the story would be limited to the reader’s perception of the action of the novel viewed from a phenomenological perspective, or as Bellow would have it, from the ebb and flow and lived experience of Artur Sammler’s first person point of view.

Consciousness, in this respect, and when written, is an attempt to “imitate” a character’s immediate flow of thoughts and feelings and thus plays a significant function since what is selected by the narrator as the “conscious” structure of Sammler’s experience is what the reader also is obliged to pay attention to and thus becomes the content or meaning of the novel.

There are times, furthermore, when the central character recedes for the moment and the narrator comes forward with background information. James called this technique “fore-shortening.” Bellow’s novel, for example, does much the same, raising its opening curtain as follows and with the narrator’s commentary:

“Shortly after dawn, or what would have been dawn in a normal sky, Mr. Artur Sammler with his bushy eye took in the books and papers of his West Side bedroom and suspected strongly that they were the wrong books, the wrong papers. In a way it did not matter much to a man of seventy-plus, and at leisure. You had to be a crank to insist on being right.”

To be sure, the “central consciousness” is not always alone but also surrounded by “satellite” characters who exhibit unique traits but revolve, so to speak, around the central character who in the instance of Bellow’s Mr. Sammler’s Planet is again the above mentioned Artur Sammler (named after Schopenhauer and the author of The World as Will and Representation), the center, and a plethora of unusual satellite characters who also need to be understood in their comic-tragic context.

For example, still early in the novel Sammler is in dialogue with his niece with whom he shares an apartment: Margotte, aging widow of Arkin who knew how to make Margotte shut up but who was currently prepared to discuss issues all day and from every “point of view with full German pedantry ” (15). She, too, is a survivor having been rescued from a refugee camp after the war and lives on war reparations from the German government. A week or so ago the dialogue between the two, was, as far as the novel is concerned, a non-apologetic venture into ideas, specifically whether evil is or is not banal. Margotte has been captured by what she understands as Hannah Arendt’s treatise on the banality of evil which has over time become something of a cliché although what Arendt meant was that if a crime against humanity had become in some sense “banal” it was because it was committed in such a normal daily way, systematically, and without opposition had become “banal.” It was, in other words, so normal when implemented by the nazis that it became an act without moral revulsion or indignation or resistance.

“‘The idea being,’ said Margotte, “‘that there is no great spirit of evil [since a] mass society does not produce great criminals’.”

The common fate, in other words, also of Socrates and Jesus.

And against this argument Sammler makes a virile interruption.

“The idea of making the century’s great crime look dull is not banal. The banality was only camouflage. What better way to get the curse out of murder than to make it look ordinary, boring or even trite” (16).

Murder is as old as the sum total of human knowledge as Genesis makes clear.

What kind of humanitarian reasoning, philosophical and legal, has been so devised to produce and protect such genocidal thinking which Sammler finds an outrage rage insisting that if Arendt’s argument was to be pursued, no one, especially Jews, would be saved from moral revisionism. For Arendt and Margotte to think that Eichmann et al were mere functionaries is to forget they were monsters and to excuse a man who believed that the death of five million Jews on his conscience gave him extraordinary satisfaction is behind contempt.

The man was an eager murderer and to make the century’s great crime look dull is not banal.

Sammler continues to respond to Margotte but by extension, Arendt.

“‘Banality is the adopted disguise of a very powerful will to abolish conscience. Is such a project trivial? Only if human life is trivial. This woman professor’s [Arendt] enemy is modern civilization itself. She is only using the Germans to attack the 20th century—denounce it in terms invented by Germans. Making use of a tragic history to promote the foolish ideas of Weimar intellectuals.”

And although there was much to be admired in the Plancks and Einsteins, Sammler had never mistrusted his judgment where the Germans were concerned. But to be sure, the strain of Margotte’s unrelenting effort gave Mr. Sammler a headache (21) .

To be sure, however, there’s something impressive in Mr Sammler’s polemic in which his insights, quite frankly and on American conservative terms, argue for a moral response to a moral problem.

VI. What Philosophical Insights Are Being Offered?

Sammler is aware that once a moral response has been breeched there is likely no turning back. In his own case history, Sammler was taken with his wife to a mass grave, stripped naked, and then with many others shot. He had, also, been struck in the eye by a German soldier with the butt end of his rifle leaving him blind in that eye. With the others, he tumbles into the mass grave but after hours of time crawls up and out of the mud and blood, naked and cold and hungry. He’s rescued by a Polish samaritan but to continue to survive he’s obliged to live in cemetery mausoleum.

His experience is real and not an abstraction in the big realm of philosophical ideas. Thus in the word pairing between Sammler and Margottte, his “I” to her “You,” he disqualifies her argument drawn from Arendt that evil is “banal.” Sammler, rather, has experienced a very ripe consciousness of evil, its darkness, its foulness, its lurid baseness. His experience is that of an “I and It” word pair in which the “I” is the German executioner who has blinded him in one eye and him as an “It” who has become dehumanized to the extent of being analogized with vermin.

The discussion between the two, therefore, reveals a moral question in which the “It” is incapable of being raised up into a realm occupied by another pronoun and with whom even the most mundane of discussions would acknowledge the finite human consciousness of another although not at the level of an absolute value, but the level in which there’s no confirmation of another person’s rational soul.

Buber thus again acknowledges the abyss that exists between an “I” and a “You” which can degenerate into an “I” and “It” to the extent that the meeting between the word pairs has lost all sanctity. Consider for a moment when the “Other” in the dialogue has been transformed into an old man. Since an old man serves no progressive purpose, the “I” holds no loving responsibility for the “Other” and any hope for sacred dialogue between the “I” and the “Other” degenerates.

What’s also missing is the dialogue that would illustrate the “I” as calling to the “Thou” not to blaspheme but to experience the fullness of being surrounded by God who dwells in us but we speak to Him only when speech and argument die within us.

VII. Genocide In The Lecture Hall….

We are not talking about genocide war crimes here but in ordinary civil society there’s a clear distinction between ideas and what we might call linguistic violence albeit the latter without prosecution.

A bit of background:

Time is usually relevant in a novel since the novel takes place in time. Mr. Sammler’s Planet, as previously mentioned, takes place in the waking moments of one day in 1969 and concludes in the waning hours of the third day suggesting again 72 hours. The exact time is roughly parallel to the American moon landing which becomes an analogy to the cultural context of that time in American history. The overall context is Artur Sammler’s consciousness again and that with which he agrees and that with which he disagrees.

He’s opinionated but so is Saul Bellow’s narrator whom one might suspect has arguments with various and sundry who in the late 1960s attempt to define a non-repressive civilization by “eschatologically” forming an “immanence” which sets forth a psychoanalytic interpretation of culture and history.

When Norman O. Brown’s Life Against Death, for example, appeared it made its way into the popular mantra of college and university young people who, so went the argument, were interested in opening new spaces for understanding and potential, neé, radically transformative ideas, new vanguards of interpretations.

Thus, likely unknown to many these days, Brown’s Life Against Death was well known by many of my age during those late 1960s years, and progressively celebrated since the book articulated alienated youth discontent. The problem, then, which bears resemblance to much of what is happening in our own time, is that so many 1960s confused youth were in revolt and bent on attacking western civilization not with prudent thought but explosiveness, abusiveness, and which Sammler describes as “tooth-showing Barbary ape howling” (43). I don’t recall anyone throwing excrement from trees but there were numerous examples of dirty slurs.

Still near the novel’s beginning, for example, Feffer the “I” comic manipulator, convinced Sammler to offer a lecture, a reminiscence to a Columbia audience. Sammler had been promised a small group assembled in a seminar room. It was instead a mass meeting of students in a large lecture hall and where Sammler was obliged to speak on Tawney, Strachey, Orwell, and Wells, old books. Standing room only but when his one good eye took in the room the audience not only looked shaggy but the aroma was malodorous. There he was, then, a microphone hung around his neck, speaking in his Oxonian manner when he was shouted at by a young man in dirty blue jeans and a thick beard, “a figure of compact distortion” (42 ).

“Hey! Old Man!,”

And as it went on the thick bearded young man yelled out that what Sammler was saying was “a lot of shit.” And it went on again with no one defending Sammler. The shouting from the audience became hostile.

Sammler was not so much personally offended by the experience but was struck by the will to use language to offend. It was also brutal but seemed to be accepted at the university as ordinary discourse, free speech, of course, but what is free speech unless accompanied by the heritage of common law.

He was saddened by the fact which led him to feel separated from the rest of his species and the “idea” that perhaps he had become an old bore, an old man.

But the worst of it, Sammler thought, was that from the point of view of the young people themselves they acted without dignity. They had not acquired the view of the nobility of being judges of the social order. What they had acquired were some uncritical notions from Brown and others without questioning but had become a new vanguard of interpretation without the benefit of tradition or disinterestedness.

The requirement should be to speak speak respectfully, and with civility. Students shouldn’t direct foul language at an invited speaker or their classmates. Respect means not interrupting and avoiding theatrical disapproval. Not to do so is abhorrent.

The point is that a human being, valuing himself for the right reasons, is duty bound to restore order and authority because all the parts must be in order, or so thought Sammler.

But someone had raised a diaper flag and someone had made shit a sacrament.

There are points here Buber would likely make.

One is that Feffer the manipulator, the “I” has disrespected Sammler for his own financial purposes. He was not present at the lecture. Sammler has not been beaten with a rifle’s butt stock but by something akin to linguistic genocide at least in word and form. No mutuality can unfold between Sammler and his audience which includes the shouting young man.

Two, is the shouting un-named young man who owns an assured 1960s intellectual position—even if revolutionary—shallow and committing linguistic genocide? He has denied even a respectful relation between his own “I” and Mr. Sammler who is is for all purposes a “You” vectoring toward an “It,” someone as a teacher denied of all his strivings which in his life have humanly affirmed him.

What kind of relationship exists between a teacher and his student if neither recognizes the other as a “You” or one would hope as a “Thou” and thus a process that denies full mutuality. Sammler in front of this audience has, one might argue, been intellectually if not spiritually murdered.

Here are some samples of the narrator’s and Sammler’s thinking once again on the morning the novel begins:

… “what was formerly believed, trusted, was now bitterly circled in black irony. The rejected bourgeois… stability thus translated. That too was improper, incorrect. People justifying idleness, silliness, shallowness, distemper, lust—turning former respectability inside out” (9).

“Such was Sammler’s eastward view… in which lay steaming sewer navels…. Little copses of television antennas… graceful thrilling dentrides drawing images from the air, bringing brotherhood, communion to immured apartment people…. But then he was half blind” (9).

“He was old-fashioned” (18).

“What better way to a get the curse out of murder than to make it look ordinary, boring, or trite? With horrible political insight the [Germans] found a way to disguise the thing…. But do you think the Nazis didn’t know what murder was? Everybody (except certain bluestockings) knows what murder is. That is very old human knowledge” (18).

“The best and purest human beings from the beginning of time have understood that life is sacred. To defy that understanding is not banality. There was a conspiracy against the sacredness of life. Banality is the adopted disguise of a very powerful will to abolish conscience….” (18).

“All the old fusty stuff had to be blown away… so we might be nearer to nature [and to be] nearer to nature was necessary to keep in balance the achievements of modern Method” (19).

Sammler was at this moment in time perceiving different, contemporary developments. The labor of Puritanism was now ending. The dark satanic mills changing into light satanic mills. The reprobates converted into children of joy, the sexual ways of the seraglio and of the Congo bush adopted by the emancipated masses.

Sammler’s own private conclusions?

He believed he was witnessing the increasing triumph of the Enlightenment… the struggles of three revolutionary centuries being won while the feudal bonds of Church and Family weakened (32).

Dark romanticism was now taking hold and the trouble was very deep. Like many people who had seen the world collapse once, Mr. Sammler entertained the possibility that it might collapse twice (33).

Apart from youthful admiration for Brown add Bellow’s /Sammler’s equal disgust with Maslow’s self-centered concern with self-esteem (above all else), and Marcuse, especially One-Dimensional Man, and the result is the oppositional thought and behavior of many opposing the prevailing traditional American way of thinking. Sammler offers a critique such that Mr. Sammler’s Planet is a rebuttal and likely the first neoconservative novel in our time as well as a philosophical critique of bad ideas that obviously have bad consequences.

Brown, Maslow, and Marcuse are of course more likely than not existential thinkers deeply engaged with their versions of philosophical and political dialogue albeit revolutionary.

VIII. Genocide On The Cross Town Bus….

With the novel, then, we are again at a contemporary moment of time, New York, shortly before the 1969 moon landing. It’s again also morning and Sammler is awakening to “consciousness” but “conscious” of what? The novel states that he’s become aware of his conspicuousness. For some reason, he’s beginning to think that there’s something about him that is attracting attention which we know is making him uncomfortable.

One reason is that his Oxonian manners and etiquette are at odds with those around him. Oxonian in that respect pertains to Oxford, England, the University, and where everyday behavior is polite and formal and cultured and learnéd.

But for those around him those manners are more eccentric than not. His wardrobe, although a bit worn, is British academic. He goes nowhere without his rolled umbrella which he holds out in front of him as he crosses the street often against the traffic.

There’s some interesting finger-pointing here revealing that for Sammler something has gone wrong which means his reflections have taken a neoconservative turn. High culture has gone awry. And like many people who had once seen the world collapse, Artur Sammler is with his morning coffee entertaining the possibility it might collapse again.

It’s also one more moment in Sammler’s days in which he struggles to make sense of New York life which he finds more and more overwhelming. On his way home on the crowded bus, to add vulgar complexity, he watches a sveltely dressed black pick-pocket he has seen on his previous bus journeys. Observed, the black man follows Sammler home and exposes himself in a threatening manner in the lobby of his building. The pickpocket, is an “I Sammler is an “It.”

Embodied by a man who points his “lizard-thick curing tube,” at Sammler who’s reduced by an “I” to the same sort of “It” the elderly man once endured in the extermination camps.

It’s the terrible insanity of a megalomaniac but with clothing that belies a certain princeliness, purple sundial shades, majestical clothing but but also a mad spirit or parasite. Sammler has watched and observed the “mugger” for some time with his one good eye and is both fascinated and appalled. and the moment comes in which the pick-pocks corners Sammler with his forearms against his throat. He unzips his fashionable trousers and takes out his member and forces Sammler’s head down to observe, to take note, to fear, to understand that this “I” has for the moment reduced Sampler to an “It.”

It’s an overwhelming and crushing scene for a man who was once buried alive under the corpse of his wife and who once again is enforced to endure. Is it, however, merely the romance of the outlaw or is it the same kind of bold criminality that has brought on so much horror in our own time?

Bellow does not spare the reader the grotesqueness of the scene which is arguably following along with the essence of Buber’s thought which judges human relations in an age in which human worth is increasingly demeaned, reduced to a thing among things. It prompts the reader to respond to a scene far removed from any enhancement of human dignity but rather shorn of any firm intellectual or spiritual footing. What is it other than an example of the tottering of social and ethical standards that one should follow with inner conviction. There’s no sacred bridge between an “I” and an “It” and with no sacred bridge no genuine human relations.

When Sammler reports the crime to the police, he’s dismissed by the officer in charge. The police are too busy with something so picayune. He has told the police sergeant his name but the sergeant calls him “Abe” which can be understood to be an anti-semitic canard.

What Buber emphasizes in I and Thou is that every day life is confronted by brute realities but to rise above those brute realities is to understand that a person’s relations with fellow human beings is equivalent to those with God.

Mr. Sammler has, rather, been surrounded at this 1969 moment by a plethora of modern characters who surely represent the betrayal of civilized ideals and tend to treat those around them as partners without reverence, drifting one might say between an “I-You” or worse yet, “I-It.”

Has the world gone crazy? There’s plenty of evidence.

The question is whether a human being deserves, first of all, to be called with the mindset of an “It.” If so, then the encounter of one human being with another will not be a genuine encounter with another with any kind of intimacy which is of course suggestive of the nauseating atmosphere of Germany in the 1930s and into the 1940s.

With that in mind, the Holocaust represents the ultimate triumph of the “I” reducing human beings to mere things.

Here one might share a prejudice of our own time and Mr. Sammler’s which is whether we suffer from too much progressive “enlightenment” and its moralizing critics with their proclaimed superiority to history and human frailty but which have created liberated persons ignorant of their very ignorance.

First is to realize again the violence done to Mr. Sammler who was forced by the Nazis into a pit of corpses along with his murdered wife and buried alive only to climb out of the mud and blood of death pit naked only to survive in a mausoleum but hunted by his countrymen, Polish anti-semites except for another Polish “human being” who fed and clothed Sammler and an example of an “I” who understood that Sampler was not an “It” but a “You.”

For the remainder of the war Sammler was a Polish partisan who at one time disarmed a German soldier and ordered him to take off his clothes. The soldier begged for his life. The man was dirty and grimy as if he was already marked for being lost, “no longer dressed for life.” He had children. Sammler pulled the trigger. The body lay in the snow; he pulled the trigger again and the German’s skull burst; blood and brain matter flew out spattering the snow.

With that example in mind the thread of the novel brings into acute focus Sammler’s own basic wisdom with German and Polish anti-semitism but his own acute and admitted joy at committing murder. For him to kill the man in the snow means that he, too, was capable of an “I-It” murderous pleasure.

When he recollects his own guilt, his own ambivalence increases when as a journalist he spent time in Israel during the Six-Day War, Gaza, blackened Arab corpses dead but not by a violence done by him but by the powerful Jewish state which he worries has the strength to make the Jewish people into oppressors, even ecstatic murderers of Palestinians which would make the Jewish folks racist killers.

To burst into genuine life is it necessary to murder, to commit a dark action? In a bleak sort of way this emotionally packed novel portrays and decodes the times. Mr. Sammler, in an ironic way, is the man who guides the reader through these comic and tragic times. At one point Sammler argues that the prophet Isaiah himself would have been funnier if he only disregarded the sexual madness overwhelming the world.

Has the world gone crazy he again wonders. There’s plenty of evidence such that one might wish to escape this world and like H. G. Wells and embark on a planetary voyage and find a new home and begin again.

Like much else in man’s utopian hopes, sheer silliness.

IX. The Final Epigrams….

Perhaps there’s more to it, the “Thou” found in the conclusion.

Joyce Carol Oates has written presciently that the conclusion is the result of a slowly building epiphany which forces the reader to re-read the novel since the reader has been altered in the process of reading the novel and thus with the conclusion prepared to begin truly reading.

One could, however, say that of most masterpieces.

She may be right but it’s important to note that at the conclusion Mr. Sammler speaks to God which offers the argument that such is an act of faith and that such a dialogue is what faith means, very ancient and very eternal, and a “primal” dialogue between an “I” and “Thou.”

And if epiphany is the right word, as in a manifestation of religiosity, Ms. Oates is on point since the conclusion narrates a subjective experience that owns a sacred dimension.

My own sense, therefore, is that something more needs to be brought into context lest the novel become another “Jewish” novel even if from an American perspective and not just one more novel of either ethnic or gender identity or for that matter a sub-category, a “holocaust” novel.

The scene at the novel’s end takes place in this dramatic way.

Artur Sammler’s nephew, Elya Gruner, has succumbed to an aneurysm. Sammler has been anxious to be with his nephew before his death but tragi-comic circumstances have prevented. A nurse escorts Sammler to the hospital’s post-mortem room where an autopsy will be performed. Elya has been laid on a stretcher. Sammler pulled back the sheet and looked down on his nephew’s face.

And then, in a mental whisper, Sammler says in beseeching prayer, “Remember, God, the soul of Elya Gruner…. At his best this man was much kinder than at my very best I have ever been or could ever be. He was aware that he must meet, and he did meet—through all the confusion and degrading clowning of this life through which we are speeding—he did meet the terms of his contract. The terms which, in his inmost heart, each man knows. As I know mine. As we all know. For that is the truth of it—that we all know, God, that we know, that we know, we know, we know” (313 ).

X. Removing The Wax From Our Ears….

In the simplest terms, the purpose of the novel is to address human existence and human relationships. Whether there is “meaningfulness” in that existence and human relationships and human meetings is dependent upon dominant modes of perception. There are also novels with an additional premise: human life finds its “meaningfulness” when we believe that all our relationships bring us ultimately into an “I and Thou” relationship with God. A very fine case in point then is Saul Bellow’s masterful Mr. Sammler’s.

Martin Buber concludes I and Thou with these words:

“Often enough we think there is nothing to hear, but long before we have ourselves put wax in our ears.

The existence of mutuality between God and man cannot be proved, just as God’s existence cannot be proved. Yet he who dares to speak of it, bears witness and calls to witness him to whom he speaks—wether that witness is now or in the future” (126).

Martin Buber died in 1965 while living in Jerusalem. Buber believed that the meeting between “I” and “Thou” was the most important element in human experience and which makes us fully human. One must, however, show up and begin with a greeting:

“Hello God, it’s me.”

Saul Bellow died in 2005 and is remembered as a writer about conscience and consciousness and the conflict in our times between the two. My sense is that his faith was genuine even though he once remarked to an interviewer that his prayerful requirements were trivial.

“I don’t bug God,” he said.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News