We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Truly the violin is a product of all that is best in Western culture: the love of beauty, the cultivation of craftsmanship, studied discipline, and sublime spirituality.

The violin has long had an honored place in the tradition of Western music. Like Western culture itself, it has traveled all around the world: for popularity and wide distribution its only serious rival is the piano. The violin and the piano are complementary, but very different, animals. The melodic “voice” par excellence, the violin is the singer among instruments. The piano, an entire orchestra compressed into a wooden box, is “the most perfect instrument” as per George Bernard Shaw.

But despite the piano’s versatility and all-encompassing nature, and the exalted claims made on the behalf of the organ, I would propose that the violin is the emblematic musical instrument of Western civilization. Precious, portable, treasured as an art object, and supremely difficult to play well, the violin is perhaps the most human instrument aside from the human voice itself. The violin’s depth of expressive capacity is related to its richness of inflection, which comes from the variety of touch of the bow, an extension of the arm and an analog to breath for the voice. The violin’s emotional range is great indeed: it can weep or dance, excite fear, exclaim, or charm and flatter with an infinite variety of accents. With its pleasantly warm and highly flexible sound, the violin (when expertly played) wears very well. And for all these reasons, it has been one of the major vehicles for expression in Western music.

Many have been the composers, performers (they were often one and the same person), and artisans who developed and expanded the range and capacities of the violin through the ages. From its origins during the Renaissance (the first surviving examples of a true violin date from the 1550s), makers in northern Italy perfected the instrument’s form and sound.

Most hallowed of all are the names of Amati, Stradivari, and Guarneri—the Big Three of classical violin making, whose instruments are cherished the world over. It was those three craftsmen/families who established the shape of the violin, with its elegant curvature, its carved details, and its varnish in hues ranging from chestnut to cherry to golden yellow.

The violin as we know it today evolved from the medieval vielle or fiddle, which in its turn goes back to the early medieval Byzantine lyra, perhaps the earliest bowed stringed instrument in Europe. The bowed fiddle has been traced further back to the Arab world, to India and China. In Greece, when Pythagoras twanged his string and discovered the correspondence between divisions of the string and divisions of the musical octave, he discovered the basic principle of violin fingering.

The modern European violin had fairly humble aspirations at first, accompanying dancing or doubling the voices in a sacred motet. The violin may have an ultra-refined image now, but at first it was something of a rustic bumpkin, a barroom brawler—just think of its countryfied version, the fiddle, alive in many cultures and probably predating the violin as a “classical” instrument.

It wasn’t long before violinists set their sights higher, realizing the violin’s potential as a solo star, coinciding with the beginnings of opera and individualistic expression in Western music. The violin (as well as its siblings, the viola and cello) could “sing” like no other instrument, could emulate the varied inflections of the human voice, and could delight the ears with flying bow- and finger-work. The violin became an instrument of a humanistic, a humanly expressive, art.

During the 1600s composers in northern Italy and southern Germany pushed the violin to new heights, writing sonatas in the “fantastic style” and exploiting the instrument’s ability to dazzle and awe. Around 1700 there was a turn to a sweeter style with Arcangelo Corelli, the “archangel of the violin” whose sonatas and concertos established a classic ideal for violin music. But in truth, both the angelic and the demonic would remain part of the violin’s personality forevermore. The expressive possibilities of the violin seemed endless: already before the turn of the 18th century there were violin sonatas depicting birds and animals, battles, and the Mysteries of the Holy Rosary (all by Henrich Biber, one of the early wizards of the fiddle).

We may think of the violin as the “Romantic” instrument par excellence, but this is belied by the instrument’s rich Baroque heritage, which has only recently been rediscovered by players and listeners. From Corelli onward Italians like Vivaldi, Geminiani, Tartini, Locatelli, and Viotti dominated the instrument, as well as Bach with his monumental six solos (3 sonatas and 3 partitas or dance suites). With their profundity and richness, the Bach works are cornerstones of the violin’s literature.

But always the violin has been an international, you could even say a universal instrument, with violinists from every country and culture (in the 20th century, the instrument had a strong foothold in Russia and Eastern Europe). And always there was the constant theme of the violin as a vehicle for personal feeling and emotion. We are told that Francesco Geminiani, virtuoso and composer, “went inside himself” when composing his violin solos, “imagining the greatest misfortunes” as inspiration for writing a pathetic adagio. His master Corelli, it was noted, despite his moderate and seraphic temper, let his eyes burn fire-red with passion while playing; he was also said to make the violin “speak” like a human voice. We have from his pupil Geminiani a perfect statement of the violin aesthetic, true not only of Baroque Italy but for all time:

The intention of music is not only to please the ear, but to express feelings, touch the imagination, influence the mind, and dominate the passions. The art of playing the violin consists in giving the instrument a sound that rivals the most perfect human voice, and in executing each piece with accuracy, decorum, delicacy and expression according to the true intention of the music.

The expression of ecstatic exultation and joy was a priority; few instruments can soar with hopefulness and aspiration as can the violin. But neither should we forget the earthy rasp of the bow against the strings—enhanced by rubbing with rosin—that can set into motion such “affects” (a favorite Baroque term) as fierceness, passion, anger. All were part of the arsenal of effects (and affects) with which the violinist could charm, coax, fascinate, and hypnotize.

And this is not to neglect the violin’s sheerly decorative fantasy, its talent for spinning elegant variations on a melody or harmony, as heard in Corelli’s lavishly ornamented adagios. And then there is the mood of longing and yearning at which the violin excels—the heart-tugging swell of the long bow caressing the strings.

Just four strings (in those days made of sheep gut, nowadays frequently of synthetics and metal) stretched over a wooden box, and a narrow band of horsehair, attached to a bow which I like to think of as a magic rod or wand: but what a range of expression from these simple means!

Nineteenth-century Romanticism extended the violin’s technique and escalated its intensity of expression. Players were now climbing up into the upper reaches of the fingerboard. The virtuoso Niccolò Paganini astounded audiences with spectacular effects on the violin, “magic tricks” that led one to suppose he was possessed by the devil (just as, earlier, the virtuoso Giuseppe Tartini had composed his own Devil’s Trill sonata, inspired by a wild dream in which he saw Satan scratching a fiddle).

The musical genre of the concerto (pioneered by Vivaldi in Baroque times) cemented the violin’s status as prima donna. In the Romantic concertos, the violin was cast as a hero striding forth to do battle against a clamorous army (the orchestra, ever-expanding). In order to fill this role, the violin needed more volume of sound. Violin makers obliged by altering the instrument’s anatomy, thickening the sound post and base bar, re-angling the neck, increasing the tension on the strings; these operations were performed even on precious Old Master instruments. The sweet and intimate Baroque violin, with its subtle “speaking” character, became more powerful and penetrating, with a new emphasis on a lush, sustained melodic line.

All the while, in addition to its new “public” role in large concert halls, the violin continued its career as a familiar salon instrument, the protagonist of elegant soirees, where it confided emotional secrets up close to appreciative small gatherings.

To be sure, the Romantic era had its share of frivolous showboating by virtuosos, mere bags to tricks to astound a paying audience. Yet the greatest composers continued to lean on the violin’s expressive qualities and to write music of true artistic substance for it. Most of the violin’s warhorses and chestnuts were composed in the 19th century, including the concertos of Mendelssohn, Brahms, Bruch, Tchaikowsky—and earlier, Beethoven, whose concerto and nine sonatas are indispensable, second only to Bach.

The Last Romanticist

And at the end of the road of Romanticism we find the imposing figure of Eugène Ysaÿe (1858–1931), Belgian violinist extraordinaire, composer, and teacher. Ysaÿe (the unusual name is an old French spelling of “Isaiah”—pronounce it ee-ZYE) straddled Romanticism and modernism—a period of Art Nouveau, Pre-Raphaelite aestheticism, and the cult of the gothic and macabre. And the Baroque tradition still exerted a pull, as you can hear in Ysaÿe’s magnum opus, his six sonatas for solo violin published in 1924, exactly a hundred years ago.

Written in response and homage to Bach’s great six violin solos, and sketched out in just a few hours, Ysaÿe’s works sum up much of the violin’s mystique of the previous 300 years of its existence. The sonatas are imaginative, fantastical, Romantic, Impressionistic, and deeply personal. Each one is dedicated to, and tailored to the style and personality of, a famous violinist whom Ysaÿe knew and respected.

To mark the centenary, I wanted to play the Sonata No. 2 in a recital this year in my hometown. It is perhaps the most popular of the batch. Ysaÿe dedicated it to his French violinist colleague Jacques Thibaud, who loved to play the prelude from Bach’s E-Major Partita in the practice room. And what does Ysaÿe do? He “riffs” on the Bach work in his own opening movement, entitled “Obsession,” interspersing it with snatches of the Dies Irae, the Gregorian chant melody from the Mass for the Dead, written by Thomas of Celano in the 13th century. A critic has described the juxtaposition as postmodern before its time, and it’s hard to disagree. The Gregorian tune returns to haunt the tail end of the next movement, titled Malinconia (Melancholy), in which the violin weeps Romantically, sometimes playing on more than one string at the same time (the technique known as double-stopping). This could be well the aging composer’s meditation on death.

The third movement is called “Danse des ombres” (Dance of the Shades), and here the Requiem theme is combined with the rhythm of the sarabande, the Baroque dance favored by Bach. While Ysaÿe offered no explanation of the meaning of this sonata, I have my own theories, as do many other violinists who have played it. I believe Ysaÿe is being haunted by the traditions of Western music, as reflected in the hallowed heritage of the violin, and perhaps his fear of measuring up and following in the footsteps of the masters. In that slow “Danse” we seem to see the skeletons of the monks joining with the shade of Bach in dancing the stately sarabande. In the final movement, “Les Furies,” Ysaÿe invokes the mythical Furies, the Greek goddesses of vengeance, wreaking punishment on the upstart composer for trespassing on sacred ground! It is a wild ride, and a fitting conclusion to a strange and singular sonata—a sonata which could well be subtitled “The Haunting of Tradition.” And why not? Romanticism is all about subjective interpretations.

The Violinist as Curator of Culture

Being haunted by tradition, of course, is something any purveyor of classical music is apt to feel. The musician is a sort of cultural curator, keeping works of music and performing traditions alive. As it so happens, recordings of Ysaÿe’s playing have survived, and listening to them gives us an insight into the ways in which violin playing has changed. To listen to Ysaÿe play is indeed to enter another world of musical experience. Even through the crackle and hiss of the over 100-year-old recordings you can hear the genius and magic. The fact is that nobody plays the violin like Ysaÿe today. The rhythmic freedom, the emotional openness and abandon that jump out from the speakers are not quite what we prize now.

The sad fact is that today classical music-making has become rather cut-and-dried, routine, predictable. Musicians of Ysaÿe’s day made frequent use of rubato, or flexibility of tempo—holding back and speeding up at various places—in lieu of playing by the metronome. Violinists frequently used portamento, or expressive sliding in between notes—an artistic effect that strikes us today as embarrassingly emotional. And it’s true that in the old recordings you hear an unabashed embrace of sentiment, an immediacy of feeling, an emotional spontaneity that at times has the effect of aching nostalgia.

Our modern musical culture tends to place technical “perfection” above emotional communication, partly due to the great success of recording as a way to preserve musical moments. The inroads of technology have affected the world of the violin as they have every other area of life, making things more convenient but spoiling much that was artistic and poetic. Nylon strings stay in tune for a longer time than animal gut, but what of their quality of sound? Is it objectively better? Vibrato (the emotional throb in the violin tone, creating by shaking the left hand) is a spontaneous emotional reaction to the music, and can also be used to sweeten the sound and enhance resonance. But too often it becomes an automatic habit, overused at the expense of the eloquent gestures of the bow.

Violin fans complain that while in the past violinists had individual styles that could be instantly identified by listening alone, now everybody sounds more or less the same. There is a bland conformity and standardization in music as in so many other walks of life.

I see my modest role as that of someone who tries in a small way to make music live, in the spirit of the past, through research and historical insight. The violin is a vehicle for personal expression but also for the great emotions and thoughts embodied by Western culture as a whole. The great 19th-century violinist Joseph Joachim—a great friend of Johannes Brahms and the man for whom Brahms wrote his Violin Concerto—was a musician who had this sense of cultural mission in his performing. He saw an ethical as well as an aesthetic role for the musician, in keeping with the high-minded ideals of German Romanticism. When Joachim played a recital, it is said, it was as if he was opening a chest full of precious possessions for the audience to admire. He saw himself as a curator of tradition, someone who guarded the most serious works of musical art and re-presented them for the public.

As Joachim recognized, there is a certain moral and aesthetic seriousness to this mission. But above all I strive to create an airy, congenial atmosphere of enjoyment and wonder in music. One seeks to “draw people up,” but also to bring music down from a dry, academic plane of respectable stuffiness to the realm of delight and pleasure. One seeks to convey the “story,” the narrative of the music; for all music, including Western classical works commonly thought of as “absolute” or “abstract,” conveys some thought, feeling, or narrative—in other words, has a spiritual or emotional meaning that the musician must discover and make manifest.

As regards the violin specifically, I like to think of it as a sort of snake charmer, a seductive enchanter. I am ever mindful of Stendhal’s statement that “the only reality in music is the state of mind which it induces in the listener.” Once one has worked out the technical perfection in the practice room, at concert is the time to let loose, forget about “perfection” and go where the sweep of the music takes you.

The violin itself has given rise to a world of lore and legend studied and cherished by aficionados, who love to sit back and remember the great violins of the past and the great artists who drew sublime sounds from them. The relationship of a violinist to his instrument is often like that of old friends, a rider to his horse, a pet owner to her pet—a trusted companion with whom one shares countless happy moments.

My own relationship to the violin has lasted since the age of eight when my mother signed me up for lessons at the local Music & Arts store. I’ve never had any ambition to be a world-class musician jetting from place to place; my own intentions are modest and local. I give a recital or concert every so often, sometimes on my own and sometimes with my lute-playing colleague. I share my music with a local retirement community. Mostly I study, listen, and read, exploring music history and repertoire, the fruits of which I then share. To round out my recital, I’ll be adding some other unaccompanied Romantic and 20th-century pieces, all rarely heard: a sonata by the French Romantic Benjamin Godard; a Caprice by Pierre Rode, agitato e con fuoco; a short Meditation on a Gregorian chant theme by a modern German composer, Richard Klein. They are all recent discoveries in digging into the remote corners of violin solo music.

The title and theme of the recital will be “Angels and Demons.” Truly, these two characters have coexisted in every era of the violin’s existence. Fiery and demonic passion (as in Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata) are always alternating with musing serenity (as in the slow movement of his Violin Concerto). The violin gives us flashy fireworks one moment, soulful introspection the next. In visual terms, think of Delacroix’s famous painting of Paganini versus the seraphically fiddling angels in a Renaissance fresco. Both are part of the mystique, the fascination of the violin.

As a community musician, I hope to contribute in some small way to this mystique. Instead of flashy pyrotechnics, I prefer to project warmth of feeling, concentrating on resonance and sonority above all. For me, the wild gypsy-like qualities of the violin must be tempered by that fundamental classical dignity and relaxed richness of resonance.

There can be something deeply unfashionable about all this, to be sure. The culture at large has gradually abandoned the “high art” forms, which have tended to be cordoned off in a museum-like space and attended only by a select few. But by highlighting the vital, beautiful aspects of this art one hopes to show that there is nothing forbidding about it, nothing that requires arcane knowledge or extensive study. Rather I try to unlock things, make them clear and communicative. Part of the business of musicians is to give culture its freshness back.

As a music critic I spend quite a lot of time at home listening to recordings. On the rare occasions when I attend a live performance, I am reminded what an electric impact it can have. And it seems to me (though I’m certainly biased) that the violin is a particularly “engaging” instrument live, being a sort of extension of the player and involving the expressive potential of his or her entire body. To hear and see violin music being made is, for me, to be exposed to a moment of grace, a sort of epiphany.

For truly the violin is a product of all that is best in Western culture: the love of beauty, the cultivation of craftsmanship, studied discipline, and sublime spirituality. The violinist himself must image poise, elegance, coordination, and taste in the union of the bow with the violin. This is an art, centuries old, in which emotional effusion, physical strength and grace, and intellectual skill combine to bring to life the masterpieces of Bach, Corelli, or Ysaÿe for anyone who cares to listen.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

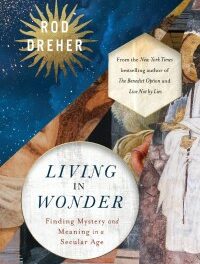

The featured image is “Young woman with a violin” (1890) by Clémence Richey, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News