We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

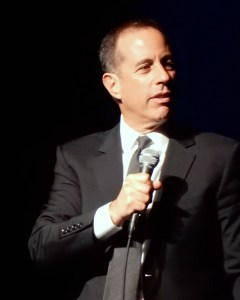

Chesterton once said, “It is much easier to write a good Times leading article than a good joke in Punch. For solemnity flows out of men naturally; but laughter is a leap.” Jerry Seinfeld did the hard work to make his show leap week after week and into history. And twenty-six years after “Seinfeld” ended, we’re still talking about it.

Seinfeldia: How a Show About Nothing Changed Everything by Jennifer Keishin Armstrong (Simon and Schuster, 2016, 308 pages)

Though the Harrison Butker commencement speech at Benedictine College in Kansas and the subsequent attempt at a media lynching has dominated the internet during the 2024 graduation session, his was not the only good commencement speech this year. Jerry Seinfeld delivered a very solid speech at Duke University, full of good humor and good advice. Though not as hot-button as that of the traditionalist Catholic placekicker, it too was countercultural in ways that shouldn’t be—but are—in 2024. He urged the graduates to do things like work hard, take a joke, and, yes, take advantage of your “privilege” if you have it.

As it so happened, Duke’s graduation took place while I was grading my own final exams and papers, so the sixteen-minute speech, combined with the trailers of Seinfeld’s new movie Unfrosted, about the creation of the Pop-Tart, had me on a Seinfeld kick. Per my usual habit when grading finals, I went off to the public library, left my phone in the car and forced myself to sit down and read essays about conscience, the limits of papal infallibility, the nature of liberal arts education, and the development of Christian doctrine. Since I can only read so many essays in a row, I usually find some easy-to-digest volume, preferably on a topic of show business or sports, to read in between creating trails of blood with my red grading pen. Naturally, Jennifer Keishin Armstrong’s Seinfeldia: How a Show About Nothing Changed Everything caught my eye.

Published in 2016, Seinfeldia was written long enough after the 1998 finale of the show named after Jerry to have lots of stories about the afterlife of the show, the stars, the writers, and even the fans to interest those who already knew the history of the show. But it tells the history, too, so that casual fans can learn something.

Though not a superfan, I’m no novice either. I’ve seen every Seinfeld episode at least once and many of them multiple times. If I can’t sleep while on a trip, I always look for episodes on the hotel television. It wasn’t always this way. I had seen a few episodes of the show in its first few seasons and found it interesting in parts but not enough so to make time to watch it or tape it on the VCR—necessary in those days of network television. It was only in the fall of 1993, when Tim Aupperlee, the Student Activities Council rep on the dorm floor of which I was Resident Assistant, told me that I had to watch the show again, that I began to tune in regularly. An original adopter of the show, Tim had been following it and had gone so far as to purchase a copy of “The Kramer,” a somewhat ridiculous portrait painting of the character, played hilariously by Michael Richards, that had been made in the previous season’s “The Letter.”

At that point, I was really intrigued. And the timing is not surprising. For, as Ms. Armstrong tells the story, the show’s survival up until then was purely accidental, filled with figures who greenlit and found funding for the show almost entirely on a whim, sometimes despite not really “getting” the show. In fact, the show’s first director, television veteran Tom Cherones, would tell actors who didn’t understand the scripts to just go with it. He understood that there was some strange comedic alchemy at work—even if he himself didn’t quite see where the show was going. And it was only by the third and fourth seasons that the gold was becoming apparent to the general public.

The irony is that neither Seinfeld nor his partner Larry David were completely sure what they were doing, either. Both veteran stand-up comedians with a little bit of experience in other forms of television, they were themselves experimenting on the basis of their vision for a different kind of comedy, fixated on the oddities of social life as they were dealt with by four shallow and somewhat vicious, but distinctly hilarious, characters that were roughly based on Seinfeld himself, David (George), Kenny Kramer (an old roommate of David’s), and Monica Yates, daughter of the well-known novelist Richard Yates (Elaine). The reigning philosophy of the show would be summarized by David as involving “no hugging, no learning.”

Though sometimes criticized as disturbing and nihilistic, this treatment of the characters was in fact a very ancient one. Ms. Armstrong doesn’t talk about this, but it was Aristotle in the Poetics who thought of comedy as the imitation of the worst kind of men (tragedy dealt with the better). Of course, David might not believe, as Aristotle did, in the corrective function of comedy, but I think Jerry Seinfeld might. The laziness of George Costanza is not the aim to which he directed those Duke students.

Of course, simply depicting the worse kind of people doesn’t guarantee that you’re making a comedy. A Stalin biopic would not be that funny. Having Stalin say, “Dark humor is like food—not everybody gets it!” is. David and Seinfeld managed to make characters who are visibly bad, even terrible in certain cases, and find the humor in their absurdity. And part of the way they did that was by making these figures attractive enough and human enough that we would identify with them and thus, ideally, begin that corrective journey that Aristotle envisioned.

By that fourth season when I started paying attention, they were attractive. While developed on the basis of real people, they had taken on their own reality. Kramer, who had originally been the dumbest guy in the room, was transformed by Richards into a kind of insane savant. George, whom actor Jason Alexander had originally performed as a version of Woody Allen, had shifted into Larry David himself and finally transformed into a distinctive character with his own mode of behavior. And Elaine, the most stable of the four characters, took off in her own zany right.

But, if character is king, as Aristotle also explained, it’s really the plot that counts. Ms. Armstrong spends a lot of time on the writers who cycled through the show, often very quickly. Peter Mehlman was the most famous. Oddly enough, he was a magazine writer who had never written any scripts that had been produced when he latched on. By hanging around the office where Seinfeld and David sat with their desks pushed together, Mehlman developed a kind of mind-meld with them and became one of the longest lasting writers—though at a certain point, he realized he was analyzing his own external and internal life for scripts to the detriment of his own emotional health. Most of the rest lasted a year or two, pitching idea after idea—mostly weird things in their own biographies—to the very picky principals who would work their magic.

What was so distinctive about the show as it started to reach the heights of popularity was itself a feature of the plot: David’s decision that all of the subplots would find their denouement together. Thus, in the famous episode “The Marine Biologist,” George has been (what else?) lying about his job. Rather than his usual “importer/exporter” claim, he has been saying he is a marine biologist because Jerry had given an old female friend of George’s that impression. Kramer, meanwhile, has found a trunk full of golf balls and been hitting them at the beach, which he has rightly been advised against doing. The end of the episode has George sitting in the group’s regular restaurant booth, relating his adventure:

I don’t know if it was divine intervention or the kinship of all living things, but I tell you, Jerry, at that moment, I was a marine biologist. The sea was angry that day, my friends. Like an old man trying to send soup back in a deli. I got about fifty feet out, and suddenly, the great beast appeared before me. I tell you, he was ten stories high if he was a foot. As if sensing my presence, he let out a great bellow. I said, “Easy, fella!”… And then, from out of nowhere, a huge tidal wave lifted me, tossed me like a cork, and I found myself right on top of him, face-to-face with the blowhole. I could barely see from the waves crashing down upon me, but I knew something was there. So I reached my hand in, felt around, and pulled out the obstruction.

As George pulls a golf ball out of his pocket, Kramer asks, “Is that a Titleist?”

It’s a classic scene—and one that David and Seinfeld came up with at the last minute. One important aspect of the show was that it was always ultimately a product for which the buck stopped at the top. Seinfeld and David worked incessantly and always had the final say on every aspect of every episode. There was no running on autopilot and no sense that it was the product of a committee. Indeed, they didn’t have a typical television writers’ room in which all the writers worked together. Instead, writers would pitch to the two, only getting to write an episode once they had been given permission. And the schedule operated according to Jerry’s and Larry’s whims.

After David left the show at the close of the seventh season, Jerry Seinfeld essentially ran the show himself. And it became even zanier in terms of plot. The realm of possibility broadened considerably. The show ended on a somewhat anticlimactic note, as the finale set records for advertising dollars but was widely seen as a disappointment. That moral element of the comedy had shown up in the group being tried in a court for their failure to help out a bystander in trouble. The trial was an opportunity to bring back a parade of former characters from the show to testify to the bad character of Jerry, Elaine, George, and Kramer.

After David left the show at the close of the seventh season, Jerry Seinfeld essentially ran the show himself. And it became even zanier in terms of plot. The realm of possibility broadened considerably. The show ended on a somewhat anticlimactic note, as the finale set records for advertising dollars but was widely seen as a disappointment. That moral element of the comedy had shown up in the group being tried in a court for their failure to help out a bystander in trouble. The trial was an opportunity to bring back a parade of former characters from the show to testify to the bad character of Jerry, Elaine, George, and Kramer.

By the time it ended, however, the Seinfeld cult had been established. Ms. Armstrong is good at showing how the show did change how television operated, paving the way for other off-beat comedies such as The Office and Arrested Development, but also how unique the show was in its success. She spends a good bit of the last few chapters discussing Twitter accounts dedicated to the show, as well as other fan initiatives and the difficulties encountered by some of the actors in recovering from their success in Seinfeld. These chapters are the least interesting part of the book and include the book’s few dull nods to the standard liberal author’s distaste for conservatives.

Despite the lackluster ending, the book is nevertheless a good one if you like the show and want to know more about its history and the people who made it run. Television is a team sport, clearly, but Ms. Armstrong’s history reveals that the success of this show was driven in large part by the bi-focal comic vision of Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David, who brought it to life by choosing the actors and pushing hard to make the show the way they wanted to. While in the early days they were protected and promoted by others, their growing success brought them the ability to do exactly what they thought was funny, no matter how obscure, weird, or unfunny—or inappropriate (I won’t defend all their storylines myself).

Purity of heart is to will one thing. Jerry and Larry willed to make the funniest show they could. They succeeded. And twenty-six years after the show ended, we’re still talking about it. Some might complain about celebrity commencement speakers, but Jerry Seinfeld earned his place as an artist of renown. Chesterton said, “It is much easier to write a good Times leading article than a good joke in Punch. For solemnity flows out of men naturally; but laughter is a leap.” Jerry did the hard work to leap and make his show leap week after week and into history.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image, uploaded by slgckgc, is a photograph of Jerry Seinfeld, taken on 2 December 2016. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News