We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

Evil, according to Christopher Dawson, is a progressive force, and it has grown mightily over the centuries since the Reformation first tore apart the West. The Reformation led to secularization, and secularization led to the creation of a machine-like society, dehumanizing all citizens of the world. The modern world is the world of the anti-Christ, with humanity existing on the edge of the abyss.

As much as the Christian Humanist Dawson wanted to write about history, philosophy, culture, and liberal education, he thought the movements of the world—especially the movement of world revolution—demanded that he spend much of his thinking and writing time dealing with one of his least favorite subjects: politics. In the 1930s—attempting to undue the ideologues of the right and left—he wrote The Modern Dilemma in 1932, Religion and the Modern State in 1935 (which he wanted to call The New Leviathan, but his publisher unfortunately vetoed it), the wishfully-entitled Beyond Politics in 1939, and The Judgment of the Nations in 1942.

It was in the last that Dawson proved most powerful—indeed, the most powerful his writing would ever be. He wrote The Judgment of the Nations as a way to cope with the Nazi and Communist hostilities of World War II. His dedication of the book—at least in the English edition of it—read: “To all those who have not despaired of the republic, the commonwealth of Christian peoples, in these dark times.” Not atypically, Dawson presents two very separate ideas in the book. The first half of Judgment deals with the history of Christendom, a rather dour look at the West, entitled, “The Disintegration of Western Civilization.” The second half, almost, at times, utopian, deals with the reconstruction of the world, presuming an allied victory in World War II, entitled, “The Restoration of a Christian Order.”

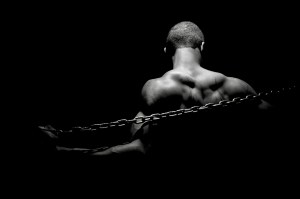

Evil, it turns out, according to Dawson, is a progressive force, and it has grown mightily over the centuries since the Reformation first tore apart the West. The Reformation led to secularization, and secularization (whether called liberalism or modernism or progressivism) led to the creation of a machine-like society, dehumanizing all citizens of the world, mechanizing nature and reality. Dawson’s prose is horrific and stunning, and one is left in no doubt that the modern world is the world of the anti-Christ, with humanity existing on the edge of the abyss. The National Socialists (Nazis) and Communists each represent the worst of human achievement, and their darkness covers the earth. These forces had always existed, but Christianity had chained them. Now, remote, distant, and far from the love of Christ and the Holy Spirit, the world embraced the demonic and Nietzschean “will to power.” In the first half of Judgment, Dawson lamented the rise of all liberalisms, seeing liberalism merely as a transition stage from Christendom to tyranny. “The advent of the machine, which was in a sense the result of the liberal culture, proved fatal to the liberal values and ideals,” Dawson stated, “and ultimately to the social types which had been the creators and bearers of the culture. The machine involved the increase of power, the concentration of power and the mechanization first of economic life and then of social life in general.”[1] Soon, Dawson feared, the entire world would be organized to the nth degree, freedom, a desire living only in the distant past.

In absolute contrast to the first half of the book, the second half considers the possibility that the pressures of the war [remember, Dawson wrote this in 1941] would force the allied powers to accept a realistic and virtuous Christianity as the means by which to reconstruct the war-torn world. Leaders, Dawson argued, must realize that culture rules the world, and that, at the heart of the culture, lies the cult, the Roman Catholic faith that baptized the classical world and inaugurated the medieval world. Christianity, Dawson continued, revels in the faith of man, in the hope of the individual, and in the efficacy of freely-chosen community. Even more, Christianity understands the Pagan Logos and makes it real for all, not just the Stoic few. It is the Catholics, Dawson believed, that not only answered the longings of the pagans but also understood the vitality of the natural law, a law that governs all alike, unifying humanity in a way organic, opposed to the mechanization of liberalism. “We are passing through one of the great turning points of history—a judgment of the nations as terrible as any of those which the prophets described,” Dawson lamented.[2] Yet. Yet. Yet! “God not only rules history, He intervenes as an actor in history and the mystery of the Divine Redemption is the key to His creative action.”[3]

In the end, The Judgment of the Nations is not just a profound work of history, it is a Christian call to arms, a reminder of all that is good, true, and beautiful in this rather fallen and war-torn world. Despite its descriptions of the horrors of progressivism, Judgment is, ultimately, a work of immense hope.

Yet, despite all of Dawson’s efforts in the 1930s and early 1940s, World War II only deepened the intensity of political dominance and discussion.

Privately, Dawson lamented in 1946: “One has to face the fact that there had been a kind of slump in ideas during the past 10 years.” Instead of thinking creatively, intelligent men had turned to realism, to science, and, especially, to politics to explain everything. “There is not only a positive lack of new ideas but also a subjective loss of interest in ideas as such.”[4] A few weeks later, Dawson wrote on the same topic, lamenting the rise of politics in all areas of thought. “There is a terrible dearth of writers and of ideas at present, and even in France, things are not too good, judging from the little I have seen.” Dawson continued. “Politics seem to be swamping everything and the non-political writer becomes increasingly uprooted and helpless.” Nothing in the world can improve if writers focus only on the sterile subject of politics, Dawson argued. The world “won’t improve without new blood and new ideas and I don’t see at present where these are to be found.”[5]

That same year, 1946, Dawson published one of his most incisive and insightful articles, “The Left-Right Fallacy,” in which he claimed the political spectrum not only false, but also as a trick of the ideologues to divide one person from another. The real divide, Dawson (along with a host of other Christian Humanists) argued, was between man and anti-man, between God and anti-god, between Christ and anti-Christ. The move toward left and right, Dawson noted, proved that totalitarian thought was slowly but surely replacing the traditional pillars of western civilization: faith, freedom, law, self-government, and liberty. Totalitarianism—as embodied by the various fascists as well as the various communists of the 1940s—was systematically undoing thousands of years of civilized tradition, bringing us back to the once destroyed systems of “slavery and massacre and torture.”[6] The western ideal “cannot work unless there is a common bond of loyalty and a will to cooperate in essentials, in despite of all disagreements and divergences of interest. This agreement is essential to the existence of a free society and consequently it is the key-point against which the totalitarian attack on Western Culture is directed.”[7] Everywhere, though, the fascists and communists seek to divide and conquer. Rather than seeing nuance, they promote absolutes, creating oppositions where none should exist. The result, not surprisingly, is disintegration. Of course, none of this is new. It is and was the tactics of the heresy of Manichaeanism, the dualistic notion of the universe, dividing all into absolute good and absolute evil.

In this campaign of disintegration the Right-Left mythology is a perfect god-send to the forces of destruction. It provides them with a crude and simple but highly effective instrument which can be applied to almost any situation and by which any number of different issues can be merged together in a mass of confusion and ideological clap-trap.[8]

In their success, the ideologues have radically increased social irrationality and division, and they’ve overpowered “men’s reason and sense of justice.”[9] Only by the intense effort and employment of the virtues of prudence and justice can one overcome the growing ideological divisions of left and right, recognizing that those calling for division are inhumane barbarians. “The way of life is the way of justice which turns neither to the Right nor to the Left,” Dawson believed.[10]

Hoping to escape the world of political domination (in thought and reality), Dawson spent much of the 1950s contemplating, most importantly in a myriad of articles, a return to Christian culture, especially through a classical liberal education. These would culminate in 1960’s The Historic Reality of Christian Culture: A Way to the Renewal of Human Life and its sequel, 1961’s Crisis of Western Education. Along the way, though, he also wrote two books that intermixed history and politics—1952’s Understanding Europe and 1959’s The Movement of World Revolution—as well as one that compiled his various essays on a profound variety of subjects, 1957’s Dynamics of World History, which ranged from serious philosophy to sociology to literary appreciation.[11]

Though Dawson had been well read by American scholars as well as American Catholics, it was his 1959 book, The Movement of World Revolution, that made him a household name on this continent. Upon its publication, Henry Luce—the owner and publisher of Time/Life—ordered a copy for each of his nineteen editors. Then, in a print editorial, “Welcome, Son, Who Are You,” Life magazine praised Dawson as a great thinker and scholar. Dawson, the editorial noted, might well be unfashionable, but Luce was willing to challenge all ideological theories with the Englishman’s scholarship.[12]

To be sure, the counterpoint of ideology vs. scholarship served as the fulcrum point of The Movement of World Revolution. Again, not atypically, Dawson divided the book in two. The first part offers a historical overview of the development of western civilization, while the second part examines the rise of western ideologies and nationalistic tendencies in Asia. Throughout, Dawson considers the role of Natural Law and, especially, Christian humanism.

In part I of the book, Dawson’s highest achievement is his successful juxtaposing of the ideologues and the Christian humanists. “Nationality has taken the place of religion as the ultimate principle of social organization, and ideology has taken the place of theology as the creator of social ideals and the guide of public opinion,” Dawson lamented.[13] As opposed to the modern ideologue and nationalist, the Christian and humanist had sought the universal, especially through liberal education—that which liberates us from the immediacies of the world.

This preservation of the old curriculum of the Liberal Arts meant that classical literature remained the basis of Western intellectual training. Virgil and Cicero, Ovid and Seneca, Horace and Quintilian were not merely school books, they became the seeds of a new growth of classical humanism in Western soil. Again and again—in the eighth century as well as in the twelfth and fifteenth centuries—the higher culture of Western Europe was fertilized by renewed contacts wit the literary sources of classical culture.[14]

For Dawson, Christianity and humanism are both well beyond ideological, being “super-ideological in character.” As opposed to traditional liberal education which makes us citizens of the world (and of the timeless cosmopolis), ideology limits the range of thought and the range of human action. It sees things merely as means to certain ends rather than things in and of themselves. In particular, “if science is divorced from humanism and Christianity, it ceases to be a creative source of culture. It is capable of creating new scientific techniques and technologies but these are the servants of the dominant ideology, which, in its turn, is the servant of a political party or dictator.”[15] To be certain, Dawson recognized that “no civilization can live by politics alone, and when a culture becomes merely an organ of political propaganda it is dead.”[16] Not surprisingly, the ideologue has really created nothing less than false religion.

True to form, Dawson ends Part I on an optimistic note. Neither Christianity nor humanism, Dawson assured his readers, were near exhaustion, whatever critics such as Friedrich Nietzsche might claim. Instead, Christianity and humanism “still possess an infinite capacity of spiritual regeneration and cultural renaissance.”[17] History has proven this time and again.

In part II of the book, Dawson successfully argues that irrational forces lurk just below the surface of democratic society, itself a façade that could break and crumble at any moment. If anything, the defeat of the National Socialists had simply lulled the western world into a false sense of security. “In our modern democratic world irrational forces lie very near the surface, and their sudden eruptions under the impulse of nationalist or revolutionary ideologies is the greatest of all the dangers that threaten the modern world. . . .”[18] In particular, the danger of excessive nationalism especially threatened the fragile democratic order. Dawson is well worth quoting at length here, as he analyzes the problem as well as attempts to find a solution in the Natural Law, itself a concrete reality no matter how often it is dismissed as a platitude.[19]

It is at this point that the need for a reassertion of Christian principles becomes evident. Nationalism is essentially a force of division; it contains no universal principle of unity or international order. If the world is left to the unrestricted development of nationalistic movements, it will become a Babel of people who not only speak different tongues, but follow different laws and seek divergent ends. As a means of evoking common action within a single society, there is no denying the value and efficacy of nationalism. But as an ultimate principle of human action, it is morally inadequate and socially destructive. Left to itself, it becomes a form of mass egotism and self-idolatry which is the enemy of God and man. This has always been realized in some degree by the great civilizations of the past. All of them have admitted the existence of a higher law above that of the tribe and the nation and consequently subordinated national interest and political power to the higher spiritual values which are derived from this source. On this point there is a consensus of principle which unites all the world religions and all the great civilizations of the past alike in the East and the West. All agree that the social order does not exist merely to serve men’s interests and passions. It is the expression of a sacred order by which human action is conformed to the order of heaven and the eternal law of divine justice.[20]

To ignore the universal is to exaggerate the particular, making a false idol of any singular group. “Indeed, modern nationalism has tended to idealize the native cultures of the Western barbarians, and to see the Germans, the Celts, the Slavs and the rest as young peoples full of creative powers who were bringing new life to an exhausted and decadent civilization.”[21] To return to the nationalisms of the barbarians, as Dawson argued, a retrograde action, moving society away from the lessons of history and civilization.

This is part II of a talk that Dr. Birzer gave for the Tocqueville Forum, Furman University, December 2, 2021. Part I may be found here. He would like to thank Aaron Zubia and Paige Blankenship for their invitation and their help.

This essay was first published here in December 2021.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] Dawson, The Judgment of the Nations (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1942), 106.

[2] Dawson, The Judgment of the Nations, 149.

[3] Dawson, The Judgment of the Nations, 150.

[4] Dawson, Oxford, to Wall, London, 26 August 1946, in Box 15, Folder 174, UST/CDC.

[5] CD, Oxford, to Bernard Wall, London, 9 September 1946, in Box 15, Folder 174, in UST/CDC.

[6] Dawson, “The Left-Right Fallacy,” The Catholic Mind (April 1946), 251.

[7] Dawson, “The Left-Right Fallacy,” 251-252.

[8] Dawson, “The Left-Right Fallacy,” 252.

[9] Dawson, “The Left-Right Fallacy,” 252.

[10] Dawson, “The Left-Right Fallacy,” 253.

[11] In 1953, Sheed and Ward also published some of Dawson’s historical essays as Medieval Essays.

[12] Editorial, “Welcome, Son, Who Are You?”, Life (March 16, 1959), 52.

[13] Dawson, The Movement of World Revolution, 84.

[14] Dawson, The Movement of World Revolution, 91.

[15] Dawson, The Movement of World Revolution, 93.

[16] Dawson, The Movement of World Revolution, 93.

[17] Dawson, The Movement of World Revolution, 96

[18] Dawson, The Movement of World Revolution, 153.

[19] Dawson, The Movement of World Revolution, 155.

[20] Dawson, The Movement of World Revolution, 153-154.

[21] Dawson, Religion and the Rise of Western Culture, 36.

The featured image is a 1911 photograph of glass factory worker Rob Kidd, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News