We support our Publishers and Content Creators. You can view this story on their website by CLICKING HERE.

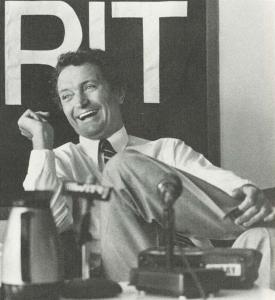

My dad brought Al McGuire to me in 1973, when I was a sick and depressed twelve-year-old kid. Al McGuire brought that same twelve-year-old girl the coolest shirt in the world, two wall hangings, season tickets, and the best thing of all: a way to hug my father.

Most girls who develop crushes confine themselves to swooning over just one young man; at the age of twelve, I fell head over heels in love with a basketball team.

Actually, this love affair began with just one fellow—he was a “college boy,” an athlete, and devastatingly handsome. His name was Allie McGuire, and his father was the Coach of the Marquette University basketball team—the Warriors. I never met Allie, but that didn’t stop me. I fell in love with his picture.

It happened on a Sunday—February 20, 1972, to be precise. Sundays were slow, long and quiet in 1972. Shopping malls and grocery stores were closed, and there was no such thing as Target. My family spent Sundays going to mass in the morning and then having dinner in the evening with the good dishes in the dining room. The hours between mass and dinner often seemed interminable; Sunday was the only day I was ever bored enough to make houses on the floor out of a deck of playing cards.

On that particular Sunday, I was sitting in the living room waiting for dinner. Sunday dinner was never something I looked forward to; whereas my mother was not averse to “going rogue” and serving English Muffin Pizzas or Spaghetti during the week, Sunday was always a roast or a ham. I hated both. As I waited for my unappetizing dinner, I picked up Sports Illustrated—in my mind, the dullest magazine on Planet Earth.

I had zero interest in sports. Gym class at Christ King School was torture; “sports” involved ridiculous and painful activities such as climbing ropes to the ceiling for no good reason, folding my (chubby) body onto a scooter the size of a postage stamp and racing to the wall in a flop sweat with arms flailing while my teammates screamed at me, or standing at the furthest reach of the outfield for softball and praying the ball came nowhere near me. That same prayer was said by every member of my team, because I had no idea how the game of baseball was played. Not understanding the game would have made it very difficult to know where to throw the ball, but that was never a problem, because I had no idea how to catch the ball. On the rare occasion that a ball sailed near me, I ducked.

Since I knew as much about basketball as I did about softball—nothing—the fact that I picked up Sports Illustrated at all testifies to how very bored I was that day. On the cover that week was a picture of the most beautiful boy I had ever laid eyes on—Allie McGuire. I turned to the page featuring the article about this fierce-looking and well-chiseled young man, and read the whole thing. By the time dinner was served, I was completely in love. I spent the rest of the night gazing at the picture of Allie McGuire, and—I kid you not–at bedtime I put the magazine under my pillow. I was in love, and I realized that my only chance to be with My Beloved would involve watching basketball. I was going to have to become a basketball fan. Love demanded it.

Sitting alongside my brothers and my parents the following Saturday, I watched my first basketball game on our black and white television. Marquette lost, but they won their next games and went to the NCAA tournament, where they were eliminated in the second round. The season was over, but I was just getting started.

More than anything, I wanted season tickets for the 1973-74 season. Marquette basketball was a hot commodity; Al McGuire’s teams were consistently ranked in the top five and McGuire was a showman. He gave the fans great entertainment value for their dollar. Students could get tickets to some of the games, but for regular season tickets, there was a long waiting list.

More than anything, I wanted season tickets for the 1973-74 season. Marquette basketball was a hot commodity; Al McGuire’s teams were consistently ranked in the top five and McGuire was a showman. He gave the fans great entertainment value for their dollar. Students could get tickets to some of the games, but for regular season tickets, there was a long waiting list.

At least, I thought, I can get student tickets. Both of my brothers were students at Marquette, and they could each buy two student season tickets, for a total of four. I babysat all summer and saved every penny I made so that I would be able to afford tickets. The line for student tickets started to form early in the morning of the day before they were put up for sale. Students waited in line for upwards of twenty-four hours, sleeping on the pavement overnight. Both of my brothers waited in the line, both got tickets, and they gave one to my father and one to me.

Tickets in hand, my father and I attended our first Marquette basketball game together in November of 1972. I will never forget the moment I walked into the Milwaukee Arena on that chilly November night. Until that game, I had only seen the games on black and white television; this place was an explosion of color, a riot of noise and festivity. The air was electric and filled with music. I felt as if not just basketball, but my whole life to that point had been black and white, and I had just walked into the color. I was Dorothy stepping out of Kansas and into Oz.

My dad and I had never had a “Daddy’s Little Girl” sort of relationship. I was the fifth of five children, and by the time I was born in 1958, my mom and dad already had a thirteen year old, an eleven year old, a nine year old, and a five year old. They had their hands full. Jack Maloney was a traditional father, the sort who demonstrated his love for me by putting on his suit every day and going to work, the kind who didn’t hug me much but made sure I had a place to sleep and food to eat and a good Catholic education. Our love for the Marquette Warriors didn’t turn either of us into affectionate buddies, but it was nonetheless something that we shared. I do not recall ever saying “I love you, Daddy!” or hearing, “I love you, Sweetie!” but Marquette basketball gave us the chance to say “I love you” the only way we knew: “They called that a foul? Are you kidding me?” Or: “Hey, Ref! That Notre Dame guy travelled! He walked! Pack a suitcase, fella!”

Sitting near me in those early days must have offered my dad—not to mention all the other fans seated near us–many opportunities for sanctity. How, I wonder now, did they stand me? I knew nothing about the actual game of basketball. What I lacked in knowledge, though, I more than made up for in enthusiasm. I heard the others cheering and tried to go with their flow; I was known to shout “gold-tending!” at random moments. How was I to know that it was “goal-tending,” not “gold-tending,” much less that it made little sense to shout it when our guard was dribbling the ball up the floor? At a certain point in one game, Allie McGuire—the love of my life—was about to shoot a free throw. I yelled out lustily, “We love you, Allie!” A young man several rows ahead turned and said, “I have examined my feelings and I do not in fact love Allie McGuire.” I ignored him. The “we” was just a cover anyway. It was I who loved Allie McGuire, with all my heart.

Watching every play with the intensity of a starved hunter waiting for a bear, eventually I learned—and came to love–the game. I arranged my high school life (I was a freshman) around the Marquette basketball season. When that 1972-73 team lost in the NCAA tournament to Indiana and their new coach, a smart aleck named Bobby Knight, I was heartbroken. Not only was the season over, but there was no guarantee that I would be able to get student tickets the following year; both of my brothers were now alumni on the wait list with all the other non-students.

Once again, I spent my summer babysitting and saving my money just in case I somehow figured out how to get a ticket, but I wasn’t optimistic. And then Lady Luck smiled on me, in the form of a big fat dermoid cyst on my right ovary that was twisting on its stem and had to come out (see “The Day a Banana Cake Nearly Killed Me” here). It was major surgery, and I was in the hospital for a week. Hooked up to many tubes, unable to eat, and in a whole lot of pain, I was one sorry sight.

The nurses at Children’s Hospital bothered me constantly, trying to get me to blow into some medieval-type bottle apparatus. The idea was to get my lungs going after my surgery, because at that point my only physical activity was moaning and they feared pneumonia. In order forestall this fate, I was supposed to blow all of the water from one giant bottle into another bottle and then back again. I couldn’t cheat, because the second bottle had a pellet of blue food coloring in it. The nurses needed to see all of the water back in the first bottle, but it had to be blue. I hated this activity with a burning passion, and I regularly refused to do it.

At some point in the Great Battle of the Blue Bottle, my father decided to walk over to the Marquette Athletics Office (which was about three blocks from the hospital), and ask for a souvenir to bribe me with so that I would make a bigger effort to win the Bottle Battle. When my dad walked into the building, he nearly walked right into Al McGuire himself. Always ready to seize an opportunity if one arose, my father told Al about me and asked for a memento. Al replied to my dad by saying, “Let’s go.” Go? Where? “Let’s go see your daughter.” Before they left, Al turned to his secretary and asked her for some Marquette memorabilia for me.

So there was my dad, walking into my hospital room and behind him, there was Al McGuire. I was still hurting, and I had been drifting in a bit of a fog no doubt caused by whatever medication they were giving me for pain. When I opened my eyes and saw Al, I wondered briefly if I had died, and was in heaven. Apparently (I heard this later), I kept saying, “Al McGuire? Are you here? Are you Al McGuire?” in a goggle-eyed sort of way.

He was there all right. And Al gave me two MU wall hangings, a shirt that said “Al’s Sixth Man,” and two season tickets, one for my dad and one for me. If someone had handed me my large and disgusting dermoid cyst at that point, I might just have kissed it.

For the 1973-74 season and for the rest of Al’s reign as coach, my dad and I had season tickets in Section 17, Row K. We never missed a game, not that year and not during the years that followed. I wore my Al’s Sixth Man shirt to every game, home or away, and whenever Al would spot the shirt, he would nod slightly in my direction and smile.

Marquette was ranked first or second in the country throughout the 1975-76 season, switching places every few weeks with the Indiana Hoosiers. Conventional wisdom was that either Marquette or Indiana would win the NCAA tournament. In those days, tournament teams were matched by the luck of the draw rather than being seeded. Also, teams were assigned to their nearest region, no matter how many ranked teams lived in the same region. Thus it was that both Marquette and Indiana were invited to the Mideast Regional; each team won its first two games and so would face each other in the regional final. Only one of the two top teams in the country would be moving on. The game was close for a while, but then Al was called for two technical fouls in a row, and Indiana used the free throws to pull ahead by eight points; they never looked back.

My dad and I were devastated. We had watched the game on television in Milwaukee, and my dad suggested that we head to the airport to greet the team when they arrived. (In this era, there was no such thing as “airport security,” and people wandered around airports at will.) By the time the players and coaches disembarked, I had been crying for hours. I was bereft. When Al saw me, he walked over and gave me a hug, saying, “Hey. Don’t take it so hard.” My sister took a picture, but I knew I would never forget that moment when Al McGuire comforted me over a loss.

My dad and I were devastated. We had watched the game on television in Milwaukee, and my dad suggested that we head to the airport to greet the team when they arrived. (In this era, there was no such thing as “airport security,” and people wandered around airports at will.) By the time the players and coaches disembarked, I had been crying for hours. I was bereft. When Al saw me, he walked over and gave me a hug, saying, “Hey. Don’t take it so hard.” My sister took a picture, but I knew I would never forget that moment when Al McGuire comforted me over a loss.

Marquette lost some key starters after their season ended against Indiana, but they were still projected to be a top ten team for the 1976-77 season. A few games into that season, though, Al resigned as Marquette coach. The team and the fans were stunned and dismayed that Al had decided to leave coaching for the corporate world. Both my father and I were distraught. The team lost three games after Al’s announcement, regrouped and started to win again, and then, near the end of the season, lost three more.

No one was sure that Marquette would have a good enough record even to be invited to the NCAA tournament that year, but they squeaked in at the last minute. The team won its first game, against Cincinnati. They won their second game, against Kansas State. They won their third game, against Wake Forest. Marquette had made it to the Final Four in Al’s last year as coach. Milwaukee was delirious with joy, and my dad and I led the cheering.

My sister Marbeth and I (she and her husband were also fans) drove downtown on a freezing cold day in Milwaukee to wait in line for tickets to Atlanta, Georgia and the Final Four. I cut my classes (I was a freshman in college at this point) and my sister brought all four of her young children. It was so cold that we had to take turns standing in line and running next door to the Holiday Inn to warm up enough to get feeling back in our hands and feet. But we got tickets, and the four of us—me, my dad, my sister and her husband—flew to Atlanta for Al’s Last Hurrah.

I was sitting next to my dad and wearing my lucky shirt in the first game when Marquette’s Jerome Whitehead scored a wobbly layup as time expired and beat UNC-Charlotte. I wore my shirt for the last time two days later when Marquette faced Dean Smith’s North Carolina team for the NCAA championship. About an hour before the game started, I was wandering around the Omni and practically walked into Al, who was getting ready for a television interview. He said, “I see you still got the shirt,” and I said “Yes, but I won’t wear it again after tonight.” He nodded a little, and smiled.

North Carolina was heavily favored to win, and for the first half and a good bit of the second, it seemed inevitable that they would be the champions. Ahead by several points, Dean Smith put his team into their notorious “Four Corner” offense. In 1977, there was no shot clock in the college game, and so whenever a North Carolina team took the lead, they would simply pass the ball around the perimeter and use up as much time as possible before taking a high-percentage shot.

Anticipating the possibility that his team would encounter the Four Corners, Al had devised a series of plays designed to rattle the players in that offense, and his plan worked. The UNC players got flustered, lost the ball and missed some shots. Marquette tied the score, forcing Smith’s team out of their offense. Marquette scored a couple of quick baskets, and the game was ours. As it dawned on the crowd that Marquette was going to win the championship in Al’s last game as coach, they began to roar. In the section where the Marquette fans were seated, the fans were crying, laughing and yelling with joy.

As we jumped out of our seats, cheering wildly, I turned to my dad and he turned to me. We had soldiered together through thrilling wins and devastating defeats. Neither of us was any good at saying to the other, “I love you,” but we had no problem saying together, “Give ‘em Hell, Al!” Our version of hugging was to shout out “Stop dribbling the ball! They’re in a zone!” On that rainy evening in March of 1977, as the final seconds of Al McGuire’s last game and first championship ticked down, we looked at each other and screamed, “We did it!” Then we hugged each other with all our might.

As we jumped out of our seats, cheering wildly, I turned to my dad and he turned to me. We had soldiered together through thrilling wins and devastating defeats. Neither of us was any good at saying to the other, “I love you,” but we had no problem saying together, “Give ‘em Hell, Al!” Our version of hugging was to shout out “Stop dribbling the ball! They’re in a zone!” On that rainy evening in March of 1977, as the final seconds of Al McGuire’s last game and first championship ticked down, we looked at each other and screamed, “We did it!” Then we hugged each other with all our might.

My father died in 1997. Al McGuire died in 2001. My dad brought Al McGuire to me in 1973, when I was a sick and depressed twelve-year-old kid. Al McGuire brought that same twelve-year-old girl the coolest shirt in the world, two wall hangings, season tickets, and the best thing of all: a way to hug my father.

I was in every way a lucky girl.

Republished with gracious permission of the author from her own website, A Saint for 45 Minutes.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Color images courtesy of the author. The featured image is a photograph of Al McGuire from News and Events, a newsletter published by the Rochester Institute of Technology (23 October 1980), and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Conservative

Conservative  Search

Search Trending

Trending Current News

Current News